‘Do you realise our names are a palindrome?’

That was the first thing Aidan Chambers ever said to me. It was 1989 and the distinguished British novelist-cum-critic was paying a visit to Sydney, and someone had arranged a kind of literary blind date for us at the Nag’s Head Hotel in the inner-west suburb of Glebe. I’d read Booktalk and Dance on my Grave, and I was feeling over-awed at the prospect of meeting their author until this tall figure loped into the public bar and — without waiting for a hello or a handshake — came out with this astonishing remark: ‘Do you realise our names are a palindrome?’

I had to spell out the letters in my head before I saw it:

AIDAN/NADIA

This mirror-imaging of our names seemed to underline the antipodal nature of our lives: spent on opposite sides of the globe.

Born in 1934, Aidan grew up in the area of north England that I know from the muscular writing of D.H. Lawrence and Ted Hughes, and when I transplant the child-Aidan into that world I imagine him being bullied for his bookishness. But I am completely wrong, as I discover when I read Aidan’s memoir (titled A Tidman Bundle and mostly narrated in the third person).

It turns out that the most significant thing about the childhood of Aidan Chambers is the fact that he couldn’t read.

Officially declared in infant school to be ‘a little slow’, Tidman (as the author’s alter ego is called in the memoir) can eventually manage to read certain simple words (‘cat’, ‘sat’) individually, but he cannot make them come together to create meaning. This learning block goes on until the evening of Friday 18 February 1944. Then suddenly, and for no apparent reason, as the nine-year-old looks at the pictures in the book he has been obliged to bring home from school for the weekend, ‘he begins to hear voices in his head. One voice is telling the story. The other voices are the people in the story talking to each other’. Although Aidan/Tidman can now read in a technical sense, he has no interest in books. A few months later, however, on a cold wet afternoon when he has nothing else to do, he opens a copy of Worzel Gummidge. Again, the prompt is a picture. Wondering what a girl is eating in one the illustrations, he begins reading in order to find out.

This time, he does not stop reading until he gets to the end of the book.

And then he does not stop reading for the next eighty years.

A little later in his memoir, the protagonist (now aged twenty and about to start teacher-training) describes how, for five years, he has known he has to be a writer: ‘I must write… I feel bad, even get ill (headaches, gut aches) when I’m not writing something that matters to me.’ [Italics in original.]

And indeed, when Aidan Chambers became a teacher, he wrote plays and short novels for his students. At the same time, he joined a tiny and unorthodox Anglican monastic order, in which he remained from 1960 to 1967.

So here are the pathways that this ‘tiddler’ simultaneously took as a young man: Teacher. Writer. Spiritual seeker.

But his true vocation was as a reader.

Over the latter part of the last century and well into the current one, Aidan Chambers was one of the most influential figures in international ‘youth literature’ (as he called it). In 1969 he and his wife Nancy Chambers started the Thimble Press, in order to publish the journal Signal Approaches to Children’s Books — which by 2003 had run to a hundred issues. The press also published critical works in the field, including some of Aidan’s own groundbreaking books of literary criticism and literary education. The couple’s outstanding service to British children's books was recognised in 1982 when they were joint recipients of the Eleanor Farjeon Award.

Unlike most critics, however, Aidan Chambers practised what he preached. His ‘Dance’ sequence of six interlinked novels are at the forefront of Young Adult fiction, in terms both of style and subject matter. On one occasion, when he was criticised for writing characters that were ‘issues on legs’, he replied that he liked issues on legs: ‘They’re called people.’

Overall, for his ‘lasting contribution to children's literature’, Aidan Chambers was awarded the Hans Christian Andersen Medal (the equivalent of the Nobel prize for Children’s Literature) in 2002.

Yet the author’s thousands of published words are only a small part of his legacy. It is in the promotion of reading — not of the mechanics of literacy, but of the actual reading of books — that this ‘slow’ reader fulfils his destiny.

* * *

A few months after that meeting at the Nag’s Head, Aidan asked me to be an Australian consultant for the publishing company that he had recently founded with Perth-based bookseller David Turton. Their aim (according to one of their promotional flyers) was ‘to publish the rare, the unusual, the extraordinary, the refreshing’, with a particular brief of making the best contemporary European children’s literature available in English. Over the course of three years, Turton & Chambers (T&C) published sixteen books translated from French, German, Swedish, Norwegian and Dutch. As sole editor and publisher, Aidan had the innovative approach of appointing a range of European consultants, employed in addition to the books’ translators, to advise him on cultural and language matters and to suggest which books and authors he might like to publish.

As T&C was a joint Australian/British venture, it always aimed to publish some Australian books as well. Here, Chambers had a number of advisors — notably academic Geoff Williams and critic-cum-historian Maurice Saxby. My job was to add the point of view of a writer. In particular, I was to let him know who to look out for among my fellow-writers.

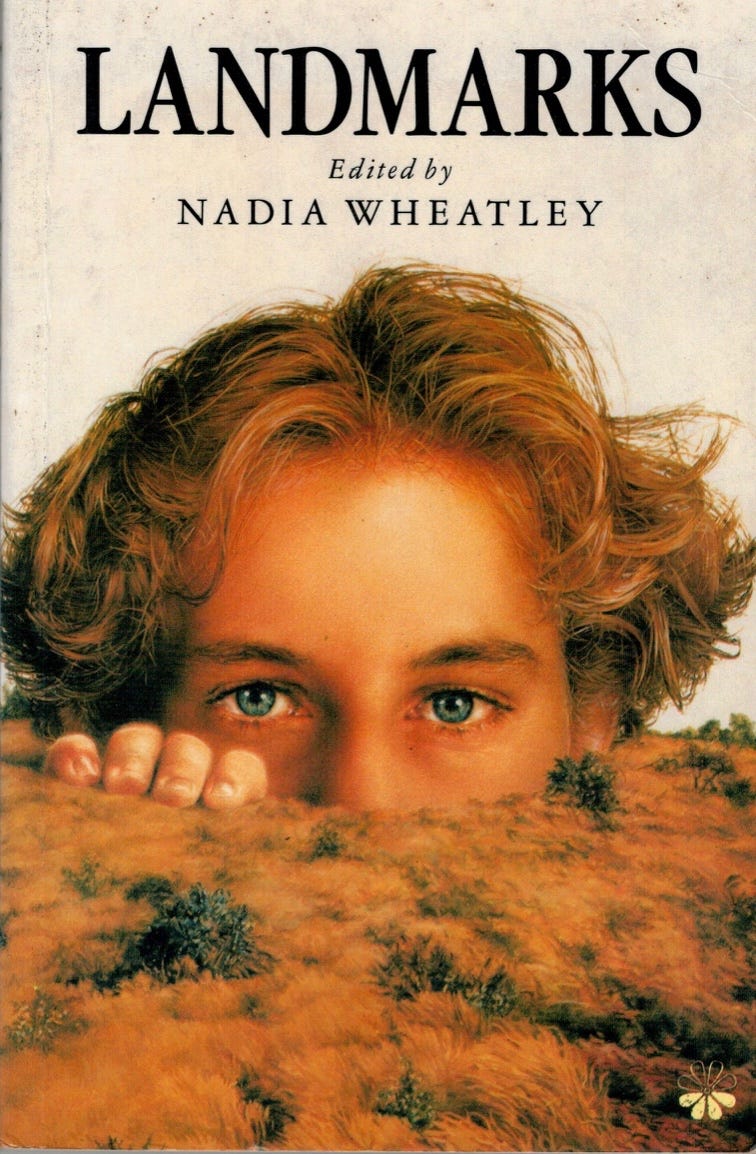

Already Aidan had contracted to publish Libby Gleeson’s novel Dodger, but to show T&C’s commitment to the Australian market he wanted also to bring out a collection of short stories by leading Australian writers. Aware that Australian English is different from the English that he spoke and wrote, he asked me to be the book’s editor. I agreed, on the understanding that Aidan would act as my sounding board and safety net.

In April 1990 he provided me with a fax machine, and we were off! I was living in the Blue Mountains at that time, and when the phone rang in the middle of the night to signal that a fax was arriving from England, I would jump out of bed and run to my office. Although our editorial correspondence went on until September 1991, it is always winter in my memory as I stand shivering in the Blackheath cold while I read the wisdom of Aidan Chambers that is coming out of the machine in a long snake-like roll. Of course, it would have been impossible to wait until morning to see what he was saying, and often I would have to start writing my reply-fax straight away.

If I include this in my remembering of Aidan Chambers, it is not to try to amplify the very small role I played in his professional life, but it is to record the esteem in which he held Australian children’s literature and its creators in that period of the 1980s into the 1990s when we were at the cutting edge of what was going on internationally in Youth Literature. The authors invited to contribute to Landmarks (as we called the anthology) are a showcase of that excellence: Gillian Rubinstein, Victor Kelleher, Jenny Pausacker, Allan Baillie, Simon French, Bron Nicholls, Libby Hathorn, Libby Gleeson, and myself. I think now that Robin Klein should have been among them, but otherwise I stand by that list. And before you complain about the lack of cultural diversity, I would like to point out that this was before Melina Marchetta came onto the scene, and also before there was a single First Nations author in our field.

Overall, as I wrote to Aidan when we renewed our relationship in January this year:

I always think of that book as a collective record of that particular generation of Australian writers, working at the frontier of YA fiction. And I learned so much from your editorial comments (whether on my own work or on that of other people). It was the best kind of apprenticeship.

This second wave of our correspondence was prompted by our mutual friend, Jonathan Appleton — author, editor, critic, publisher, and London-based Australian expat. Over time, Aidan and I had lost contact, thanks to the antipodal nature of our lives, but Jonathan — knowing I was planning to come to England in April — wrote to Aidan just before New Year, asking if we might go together to see him.

‘I wish I could say yes to a visit but not on, I'm sorry to say,’ Aidan replied, explaining that he had no idea if he would ‘still be here by April’.

Not expecting a reply — indeed, insisting that I did not need one — I wrote to thank him for all he had meant to me.

And again, we were off!

This time it was emails rather than faxes arriving in the middle of the night, and of course this time I was in summer, and Aidan was in winter. ‘Here very cold after snow,’ he noted in his first missive, which he signed off with the words: ‘Go well, stay well, dear palindrome friend.’

We could have finished there, but he asked what I was working on, and I now see that the thing that hooked him was my mentioning, in my second email, that I was writing a book about Belsen Displaced Persons’ Camp in the immediate post-war period. In his reply (sent that same day), Aidan pasted in what he called ‘the crux’ passage from his memoir: a scene set ‘April 20, 1945 or thereabouts’ when his alter ego, then aged ten, goes to ‘the town’s fleapit cinema’, to see his regular Saturday-afternoon film showing, and in between the two features, ‘the newsreel comes on’:

It shows, with the usual blustery voice-over commentary, the arrival of British soldiers at the Nazi concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen, and tours round the [unspeakable, unwritable] scenes they found there.

Those brackets are Aidan’s, and they are in the book as well. At the end of the passage included in his email, Aidan starkly observes: ‘The end of my childhood.’

After this, we swap by Express Post copies of our respective memoirs. When mine arrives at his place, he tells me: ‘Because I am a slow reader by nature and now my stamina is diminished, I will not be quick [to read it]. But, in a way, that is good because it prolongs the pleasure. Always still more to look forward to.’ This from a man who knows he has maybe only a matter of weeks left: and in fact he would die a month or so later, on 11 May, at the age of ninety.

Reading his memoir, I discover that Aidan — an only child — was fortunate in his mother (the daughter of a coal miner), who was physically affectionate and supportive of her changeling. His father (whose family was a little higher up the class scale) was a craftsman-joiner, and later worked as a funeral director for the local Cooperative Society. In the ‘Youth’ section of the memoir there is an extended journal-passage, covering a week in July/August 1952, when the narrator (then aged seventeen) and his father go on a sailing trip on the Norfolk Broads. In what seems to have been the only time of intimacy between the two, the son tries to explain that ‘When I read books that really matter to me, I feel at home. I feel that’s what I’m meant to do.’

The father responds by talking about his own early working life — leaving school at fourteen, not wanting to go down the pit, and one day walking past a joinery shop, where ‘the smell and the noise drew him in’.

‘I knew straightaway it was the job for me,’ he said.

‘You felt at home,’ I said.

He looked at me.

‘But reading isn’t a job, is it?’ he said.

It might not be, in any usual way, but Aidan Chambers made for himself a job as a reader.

I am not diminishing his role as a literary critic, as a writer of fiction, or as an educator when I say that I believe this is the cornerstone of his legacy. One of Aidan Chambers’ many expressions that have become a byword in the field of youth literature is ‘the enabling adult’. By this, he means the person — parent, teacher, mentor, friend — who opens the gate for the reader, whether into a particular book, or into the whole business of reading.

For all of us — readers, writers, teachers, librarians, parents, children — Aidan Chambers was our Enabling Adult.

Go well, dear palindrome friend.

I had not heard of Aidan Chambers - isn’t it interesting how chance encounters can change the course of one’s life, or at least add to it in wonderful ways.

Thank you so much for that Nadia, just wonderful. Aidan’s book “ Tell me” was a bible to me for 25 years.