Bloomsday (16 June) was always a milestone in Martin Johnston’s year: an opportunity to combine his love of James Joyce’s Ulysses with his enjoyment of having a few drinks with his mates.

I remember that in 1972, when Martin (then aged 24) was living in a flat above an opportunity shop on Enmore Road, he held a Bloomsday party during which the assembled mass of a hundred or so drinkers caused the towering brick-and-board bookshelves to collapse, sending the books flying in all directions. Even among a crew accustomed to being bashed by police there were a few sore heads (or maybe that was just the flagon-wine).

Bloomsday also plays a key role in the plot (insofar as there is one) of Martin Johnston’s experimental novel Cicada Gambit (written in 1973-4 but not published until much later). In this, a pompous academic from the Sydney University English Department named Dr Skogg (‘squat, hirsute and hostile’) has the annual Bloomsday habit of ‘laboriously going through as close as possible a re-enactment of the events of Ulysses’. As his secret pilgrimage to Sydney’s bars and brothels is in progress, Skogg becomes entangled with the novel’s main narrator, Vlastos, a Greek-Australian chess player (almost of Grand Master level) living in Sydney’s inner west, and with Sean McIan, ‘a very low-ranking reporter on the morning Clarion’. Both the latter characters were alter egos of the book’s young author, while Skogg embodied the characteristics that had made Martin leave the English Department in disgust after completing only one year of his Honours course.

But at this point I should perhaps include a bit of a cv, for anyone out there in Substack-land who does not know who Martin Clift Johnston was…

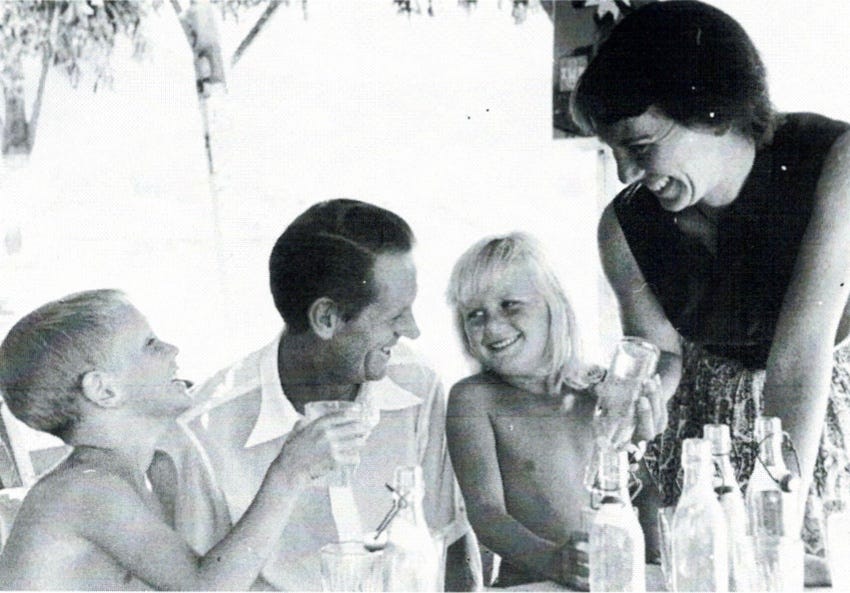

Born in Sydney in 1947, Martin was the first child of authors Charmian Clift and George Johnston. Only three years old when his parents moved to London, he would acquire at his Montessori kindergarten an accent that would sometimes make people think he was pretentious. (He wasn’t).

Worried that, in London’s urban environment, Martin and his younger sister Shane had no opportunities for outdoor play, in December 1954 Charmian and George threw in their swanky lifestyle and migrated to the remote Greek island of Kalymnos. Enrolled at the local school, Martin acclimatised so quickly that within six months he appeared on the program at the end-of-year assembly, ‘wearing a red evzone cap, brandishing a wooden sword and declaiming in perfect Greek on the joys of being a guerrilla fighter in the mountains’ (as Clift wrote in Mermaid Singing). This was the beginning of a lifelong passion for the klephts (brigands), many of whom became heroes of the Greek War of Independence.

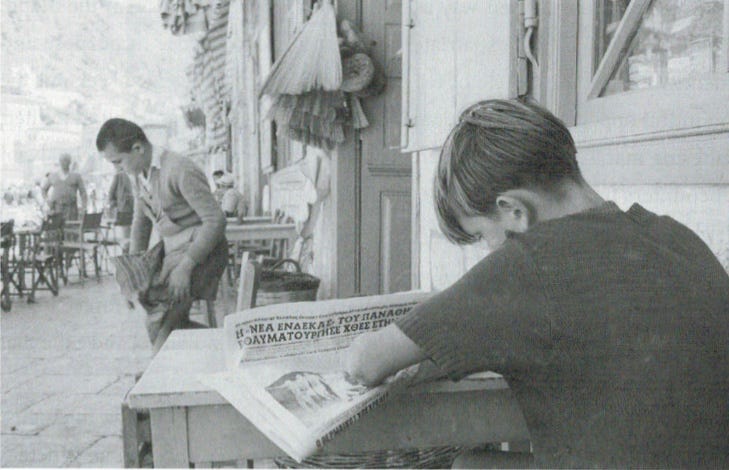

As a second winter in Greece approached, Martin’s parents moved to the cosmopolitan island of Hydra where, by the following spring, they had bought a house and had another child, given the classical name of Jason. Here again Martin was enrolled at the local school, where he would complete most of his formal education. The Greek curriculum, with its focus on history and the arts, suited him perfectly.

But Martin was further educated simply by being among the writers, artists and actors who were his parents’ friends. At the frequent gatherings at the Johnstons’ Hydra house there would often be poetry readings — either recitations from Charmian’s well-thumbed copy of The Oxford Book of English Verse, or new poems written by one of the visitors, such as an unknown Canadian folksinger named Leonard Cohen or the equally unknown Australian poet, Rodney Hall. Another significant source was Australian Bush Ballads, which the publishers at Angus & Robertson sent to George and Charmian in 1957. For ten-year-old Martin, who had no memory of Australia, the bushrangers who featured in many of the ballads seemed versions of the Greek klephts, and he proceeded to mark the poems out of ten.

In 1964, the Johnston family’s ten-year sojourn in Greece came to an end, in part because George Johnston was suffering recurrent health problems, but also because Martin’s parents wanted to give him and Shane the chance of finishing their education in the country of their birth. The family settled in the Mosman area of Sydney, and Martin — soon to turn seventeen — went straight into the final term of Fourth Year at North Sydney Boys High, where he was happy to find a few other oddballs. One of these was a boy of Greek parentage named Lex Marinos, who had grown up in the climate of prejudice common to the era. In his memoir, Blood and Circuses, Lex movingly describes how ‘Martin was the first Anglo of my own age who made me feel good about being Greek.’ He adds, ‘Martin was a misfit in a variety of ways — he was bookish, non-athletic, eccentric, kind of foreign, and, above all, he didn’t give a shit.’ In class ‘he spent his spare time translating T.S. Eliot into Greek, when he wasn’t writing his own poetry’.

In 1966, Martin matriculated to Sydney University, where he immediately took to the rambunctious life of pubs and parties and political activism. Although he was soon picking up literary prizes for his short stories and poetry, he dropped out of university in mid 1968 without completing his degree, and — to the horror of his ex-journalist father — took up a cadetship with the Sydney Morning Herald.

By now, it was clear that George Johnston’s chronic tuberculosis, contracted during his time as a war correspondent, was not going to get any better. By late 1968 he had been sent home to die. Charmian, who was carrying the burden of supporting the family emotionally and financially, was struggling to cope. In June 1969, the couple celebrated their wedding anniversary by taking a holiday together on Norfolk Island. Barely two weeks after this, Charmian Clift made a suicidal cry for help, which no one heard. A year later, in July 1970, George Johnston died in his sleep, at home.

Martin’s friend and fellow-poet, Terry Larsen, who shared a Glebe fleapit with him for a few months that year, remembers: ‘We had reading nights. Drinking nights. Eating nights. Mostly drinking. It went with poetry.’ He adds: ‘Singing and drinking seemed a solution to most problems.’

* * *

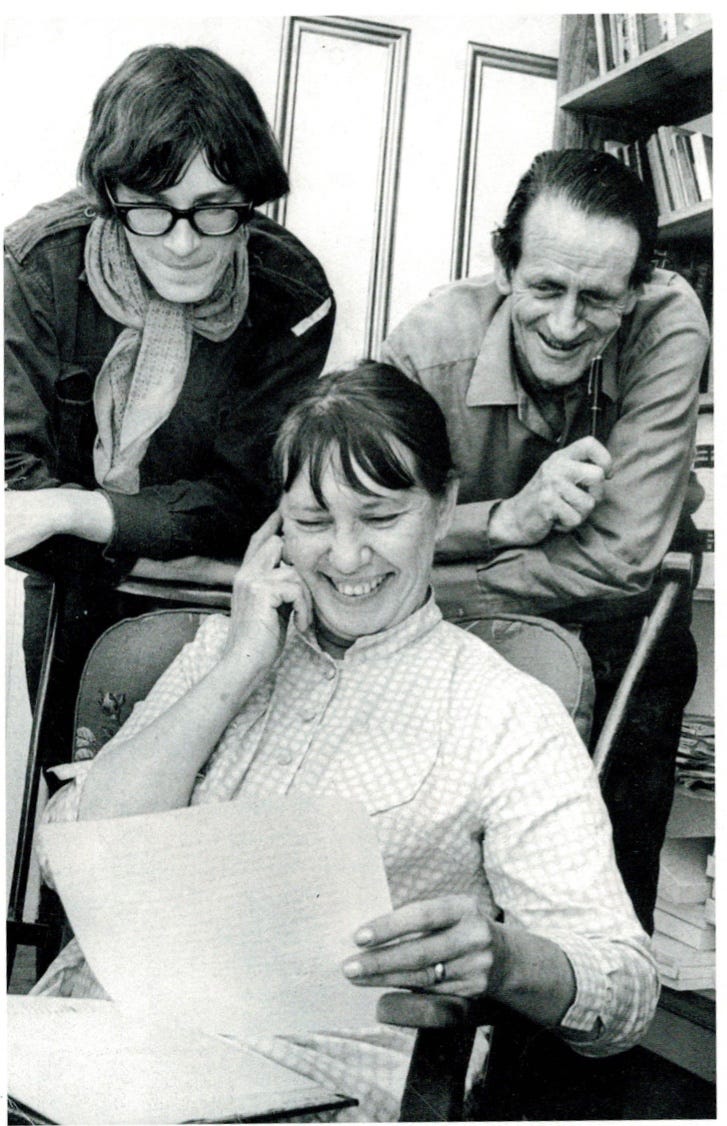

It was a couple of years later that — to my own amazement — I found myself living with Martin Johnston. And yes, he was drinking a fair bit. We were all drinking a fair bit. We were young, and the Sixties were still in full swing. But Martin was also bashing away at the typewriter for a number of hours every day.

By now, he had given up journalism, and was eking out a meagre living by producing regular book reviews for the Sydney Morning Herald. In 1973, he published Ithaka, Modern Greek Poetry in Translation. The introduction included a trenchant attack on the ‘thugs and yokels who currently run the country’. This was a reference to the right-wing Junta who had overthrown Greece’s democratically-elected government in 1967; like many philhellenes, Martin would not go to Greece while the Colonels remained in power.

In July 1974, the Junta fell. In November 1975, Australia suffered its own coup d’état in the Dismissal of Gough Whitlam. Martin and I exchanged Australia for Greece forthwith.

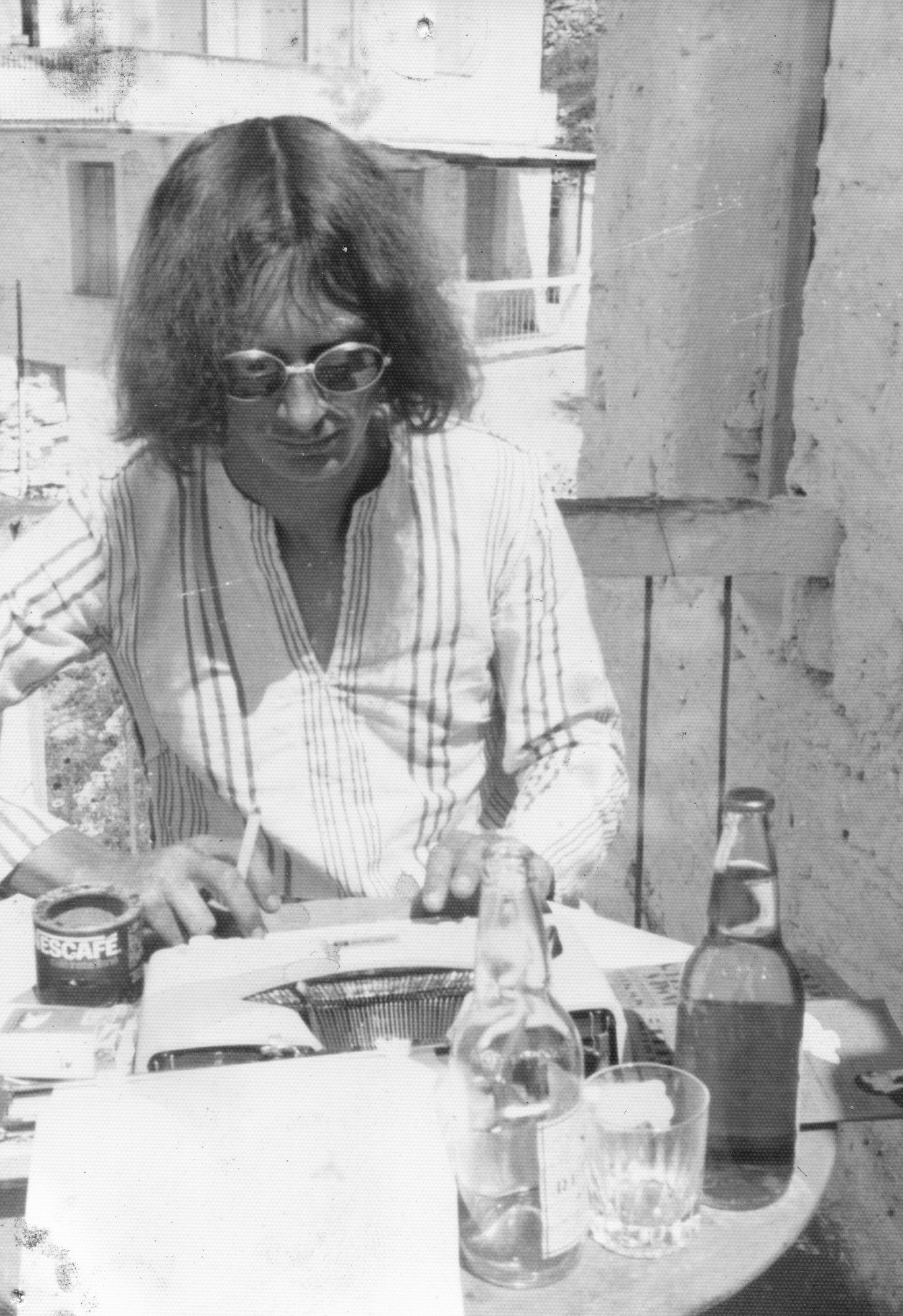

In Greece, Martin drank less, ate more, and wrote from 11 am to 7 pm, six days a week. As he would say in an interview for the National Library, ‘After a long hiatus, in which I hadn’t written all that much poetry, suddenly things seemed to be going right again. It was going back to Greece that did it.

If Greece nourished the writing we were both doing, a winter in London spelled the end of our romance. Our deep friendship remained intact, but Martin and I returned to Australia separately. It was soon afterwards that Martin fell in love with Roseanne Bonney, whom he would later marry. Martin had never wanted to have children, but he adored Roseanne’s daughter, Vivienne, who was fifteen in 1979 when he moved into their Darlinghurst household.

The next year, Martin joined the fledgling Special Broadcasting Service, where he would work as a Greek sub-titler and as a sub-editor for the next nine years. With its cosmopolitan staff and its commitment to multiculturalism, this was a place where Martin Johnston could be both European and Australian. Yet while he was loved and respected by his colleagues, he gave so much to this job that he had no creative energy left for writing. This left a hollow inside him, which he attempted to fill with alcohol.

In 1988, Martin took an extended break from SBS, and went overseas with Roseanne. While living in Tuscany and on the Greek island of Lesbos, he worked on a novel about General Makriyannis (a hero from the Greek War of Independence) and a number of poems. In a letter written to Vivienne that July, he was so confident about this return to work that he said, ‘The way things are going, it looks as if I’ll have a (totally unexpected) new collection of poetry ready for publication when we get back.’

But that was not to be.

After Martin’s return to Australia in early 1989, his drinking took on a new dimension. The recent death of his half-sister, Gae (George Johnston’s daughter), seemed part of a pattern with the deaths of his parents and of his sister Shane, who had taken her own life in 1974. Martin’s grief (expressed in a poem of that name, written at this time) was mingled with a kind of survivor guilt that caused him to talk at times as if his own premature death was also predestined. This was not helped by other people referring to the Clift-Johnston family as some form of ‘Greek tragedy’. Unfortunately, this facile perception persists to this day in sections of the media.

Over the next eighteen months, Martin’s family and friends undertook various projects to get him off the grog. Courteous as always, he put up with our efforts, booking into drying-out clinics on a couple of occasions and becoming a patient of Dr Alex Wodak at the St Vincent’s Hospital Liver Clinic.

But by the beginning of 1990 Martin was living alone in a flat in Glebe, somewhat too close to the Toxteth Hotel.

* * *

In hindsight, I realise we should have been alert to the dangers of Bloomsday…

In Cicada Gambit, the Joyce-aficionado Dr Skogg gets up on the morning of 16 June knowing (as he always did on Bloomsday) ‘that everything was going to go wrong’. Nevertheless, ‘he went ahead in the same way every year, obliviously expectant that just this once everything would go off perfectly’.

On 16 June 1990, Martin paid his respects to Joyce’s anti-hero by going on a binge with his drinking pals at his local. After a few hours, he suffered a fit, and was taken by ambulance to Royal Prince Alfred Hospital. When triage staff began their assessment by asking him what day it was, he replied — politely as always, and in his cultured ‘English’ accent — that it was Bloomsday. When they questioned him again, he insisted: ‘It is Mr Bloom’s day.’

Thinking he was rambling, the medical staff diagnosed him as suffering from delirium tremens.

A little later, a university student working part-time as a ward assistant was asked by a nurse ‘to keep one of her patients company’. When he entered the ‘partially lit’ room, he saw that the man lying in the bed ‘was highly agitated and sweating profusely and his wrists were tethered to the bed frame with rope, which was unusual (disallowed now)’. As the former ward assistant recalls in his piece ‘Bloomsday 2020’ (posted on the Martin Johnston website):

He asked me to take the $20 note on his tray to the bar 'just over there' and bring him back a drink. There was no $20 note and no bar. What struck me about this man was his accent: his manner of speaking was not that of the usual clientele of this particular ward. He told me he’d attended a Montessori school and had spent his childhood on a Greek island. Maybe there was a name tag above his bed, or maybe the narrative started to feel familiar, I can't remember which, but I said 'You're George Johnston's son.' Martin Johnston, even in the discomfort of alcoholic delirium was annoyed, as if he'd heard this helpful observation before, just occasionally…

After chatting for a while, Martin's mood brightened. He forgot the tethers on his wrists. I took his hand before leaving his room and promised to come back and see him on my next shift. Martin looked up and said, 'Yes, I would like that.' I imagined meeting Martin in better circumstances, and continuing our discussion in a cafe in sunny Glebe.

But when the young hospital employee returned a day or so later, Martin was no longer in the ward.

As he had lain unmonitored in his hospital bed, and unable to reach for the alarm button because of the tethers around his wrists, he had suffered a severe heart attack, which caused his heart to stop. When he was discovered, his heart was re-started, but he never regained consciousness.

I arrived at the Intensive Care Unit on 18 June to find Martin breathing with the aid of a machine. With great generosity, Roseanne invited me to remain with her at Martin’s bedside. I had taken his four books of poetry to the hospital with me, and I read them aloud to him, from cover to cover, over and over, during the next seventy-two hours. As the nurse kindly said when I asked permission, ‘It couldn’t hurt.’

On the afternoon of June 20, the doctors turned off the machine. The striped curtains of the hospital cubicle were closed around us.

Even without assistance, Martin’s heart beat on powerfully beneath his bony ribcage, for hour upon hour. Through that last night, as his body fought on, I kept reading himhis translation of the Greek folk ballad ‘The Death of Dhiyenis’, which describes the exploits of this hero who had ‘never feared a man among the brave’. Finally, however, Dhiyenis meets a stranger who challenges him to a contest of strength, ‘and whichever should win would take the loser’s soul’.

And they went and wrestled on the marble threshing-floor;

and where Dhiyenis struck, the blood filled a trench,

but where Death struck, the blood filled a river.

When it was over, Roseanne and I went out onto the hospital forecourt. It was the dawn of the winter solstice.

Martin Johnston’s sense of poetic timing was always perfect.

* * *

Friendship was one of Martin’s many gifts. As his fellow-poet John Tranter wrote: ‘Martin was a dear friend: kind, shy, witty, erudite, charming and endlessly generous. We were lucky to have him among us; we shall never see his like again.’

His death has not meant the end of his companionship.

In 1993, John Tranter edited Martin Johnston, Selected Poems and Prose (University of Queensland Press). This is now out of print, but in 2020, Martin’s step-daughter, Vivienne Latham, and I commissioned Ligature Digital Publishing to bring out a selection of his poems. Titled Beautiful Objects, this is available as a quality paperback. You can find the link to Ligature on the Martin Johnston website, along with a lot of information about Martin and his work. https://www.martinjohnstonpoet.com

The book was launched over Zoom during the Covid lockdown by Martin’s school friend Lex Marinos, whose moving speech was followed by a number of Martin’s fellow poets reading his work.

Every year since then, some of us have got together to read some poems — by Martin, and by other poets — and to celebrate the gift of friendship that Martin gave us. This year, we will be meeting this coming Saturday 21 June: the Winter Solstice.

In this week that links Bloomsday with the Solstice, it is good to be remembering Martin, not with grief, but with a sense of looking forward, joyfully, to what is to come. As he wrote in the concluding stanza of his poem, ‘Winter Solstice’:

Nadia this is a very generous contribution to the history of significant people in Australia back then. Such objectivity and passion. Thank you for both the details and the style.

Nadia ... what a beautiful memory

I am almost in tears as I read your writing about Martin

It makes me feel that I would have liked to have know him

Those were the days my friends

Mike