Given the amount of death and darkness lately in this Substack (not to mention the world), I thought I might have a bit of a nostalgic rave about Greek food. Or rather, Greek restaurants.

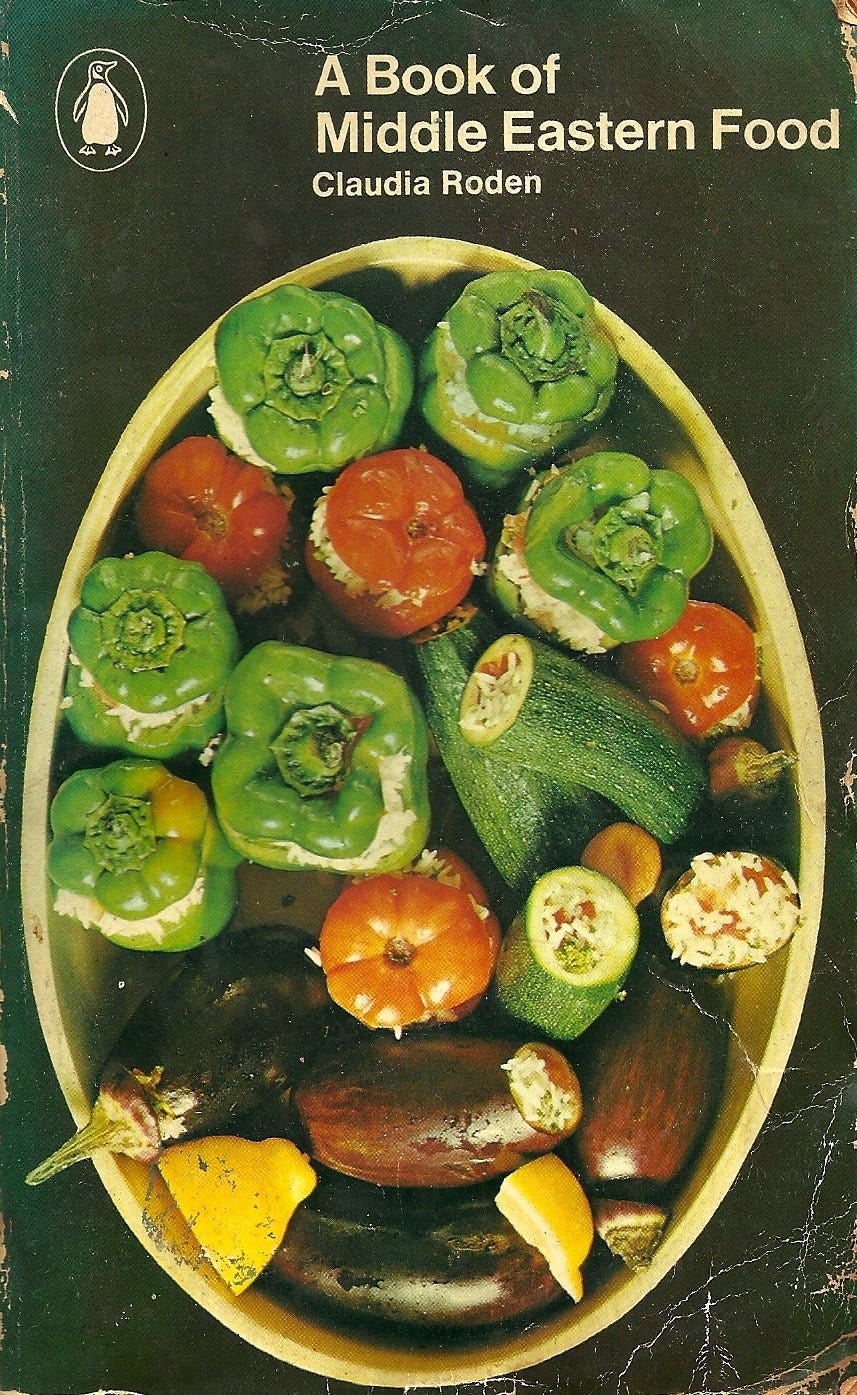

Like many Sydneysiders, I first encountered Greek food at Diethnes, which with some justification calls itself ‘Sydney’s Original Greek Restaurant’. That was in 1962, when I was thirteen, and I still remember my surprise to discover that olives were black and had pits in them. A decade later, I used to frequent the New Hellas, with its white tablecloths and posh wine list, and the Minerva, where you had to drink your BYO from thick white teacups in case the liquor-licensing police arrived. At that same time, I was working my way, from cover to cover, through Claudia Roden’s Book of Middle Eastern Food. Appropriately published in the transformative year of 1968, it was my introduction to the ingredients and cooking style of that part of the world.

As to ingredients — for the benefit of any non-baby-boomers who are reading this, I should point out that buying an aubergine or a zucchini, let alone a bottle of olive oil, could be a task in itself in the Australia of the early 1970s. Indeed, I remember once walking the length of Glebe Point Road searching for a knob of garlic. In those days, we had never heard of the Mediterranean diet. Indeed, I expect that many Australians had never heard of the Mediterranean, or at least could not have found it on a map. Chop-and-three-veg (the pea, the bean, and the potato) had served us well through two World Wars, a great Depression, and seemingly endless decades of Liberal/Country Party government, so why look for something different? Of course, left-footers had to eat fish on Fridays, but the invention of Rice-a-Riso did more to liberate Australia’s Catholic housewives than all the theological reforms of Vatican II.

By 1972, it was Time for a culinary as well as a political change, and I wasn’t the only Anglo-Australian to be stuffing capsicums. But my experimental cooking and eating was really just the appetiser for the main dish of Greek Food that began when Martin Johnston and I went to live in Greece.

First stop Chania, in northwest Crete. The winter of 1975/6. One tempestuous night when the waves were crashing over the harbour wall, Martin and I battled our way along the paralia to a sailors’ bar where Martin soon got taken up by a group of three young conscripts from the naval base at nearby Souda Bay. This wasn’t unusual — Martin being taken up by a bunch of Greek men — but it was usually the old men who would ask the Greek-speaking xenos ‘Apo pou eisaste?’ Where are you from? And then Martin and the old men would spend the night talking about politics and football. But on this occasion it was Mimi and his two mates who started the conversation that went on until the early hours. They became our parea over that winter, of which I am only going to describe one night because my focus here is food.

The five of us in Mimi’s tiny car. The drive up into the Lefka Ori, the White Mountains. The road slippery, snowy, and oh, so steep. Arriving in a village (I never knew the name). And then we were in a taverna where there was just one thing on the menu. Kounelli stifatho. Rabbit stewed with onions and cinnamon. Served with horta: boiled wild greens, with a dressing of olive oil and lemon. The best meal I have ever eaten? Possibly. And I don’t even like rabbit. (Its not the taste that puts me off but the little bones, which always seem to bring into my mind a picture of Peter Rabbit in his dear little blue jacket.)

And when we’d all had our fill of stifatho, Mimi put some coins into the juke box and he and his two mates danced the pentozalis, the perfect wild dance for a perfect wild night in the Lefka Ori. (Martin translated the name of the dance for me as ‘Five Times Dizzy’, which I would later use as a book title.

Fast forward to Paralion Astros, where we moved shortly before the Easter of 1976 and would live for the following ten or so months.

Paralion Astros, with its pretty name of Seaside Star, is in the Peloponnese, on the Gulf of Argos. At that time, the village didn't have much in the way of food. There were two grocery shops, where the only meat was tinned Spam, and Christos the greengrocer had so few items for sale that after he and I had walked three times around the premises looking sadly and silently at the withered carrots, the wilted lettuce and the rotting tomatoes, he would prise open the tin of pickled veggies: where there was a thick band of white mould on top of the murky slough of brine. Like my neighbours I mostly cooked fakes (lentils), seasoned with a scoop of tomato paste and maybe an onion if Christos had such a thing.

(‘Why not fish?’ you ask. Surely the village of Seaside Star was on the sea! Yes it was, and at night we would see the lights of the gri gri boats bobbing on the dark velvet water. Very pretty they were, too. But at dawn when they came back in, the catch was packed in boxes and trucked to Athens.)

Mostly we were fine with our limited and vegetarian diet (we were living in Greece, for heaven’s sake!) but if I felt we needed to boost our protein I used to walk five kilometres through the olive groves to the inland village of Astros, where the grocer sold frozen Argentinian mince meat in one-kilo squares. By the time I’d walked back home, I would have blood running out the bottom of my plastic shopping bag.

Alternatively, we could eat at Thanassi’s.

He was the village president, and the proprietor of the waterfront taverna. He sold grilled chops (lamb or pork) and fried liver. Also grilled fish, potato chips, and horiatiki salata (literally ‘country-style salad’, and meaning the popular combination of tomato, cucumber, onion, capsicum, fetta, olives).

The problem was not the food but the politics.

On the wall above the counter was a big photo of Costas, aka Constantine II, ‘King of the Hellenes’. You can trawl his murky past on Google, but suffice it to say that back in the 1960s he had been plotting his own coup and military dictatorship with a right-wing gang called the Sacred Bond of Greek Officers when the Colonels had pre-empted him in April 1967 by setting up their own show. Although Costas (from the safety of exile) formally inaugurated the Junta, they stabbed him in the back and abolished the monarchy in 1973. With a popular vote confirming Greece as a democratic republic in 1974, he was OUT by the time we were in Astros, but he was still on the wall of Thanassi’s taverna. A cat may well be able to look at a king but if a diner looked at King Costas with a less than adoring glance: well, there would be consequences. Paralion Astros had the reputation of having been a pro-Junta village and the local police force had not changed since the regime had fallen. As Aliens, Martin and I regularly had to have our residency permits approved. Even apart from that, we had to pay our electricity bill through the village president (with an added service fee), so we did not want to accidentally look sideways at the ex-king and live in darkness.

So forget about eating at Thanassi’s. Much better anyway to go to the place known as The Widow’s. Tucked away in the back street, it did not have a sign out the front with a name on it. It did not have a menu. What it did have was a barrel of retsina and four tables, each with four chairs. It was where the fishermen ate, and they did not need a menu because they simply took their own fish along and the widow cooked it and served it up with their retsina, and they paid her for the cooking, as well as for the wine.

Not having any fish, Martin and I would go to the grocery store and buy two eggs and the widow would cook us an omelette. We would also of course order retsina. And soon the fishermen would send us little bits of their fish, and we would send them some retsina.

So the widow’s omelettes go into my sentimental shortlist of Great Greek Food.

In the spring of 1977, we moved back to Chania, where it wasn’t long before we found a place that made the widow’s establishment at Paralion Astros seem kind of fancy. Again, there was no formal name, no sign outside. It was known (insofar as it was known at all) as The Grandfathers’, for the simple reason that every single person who frequented it was a grandfather.

Every single person, I should say, except for Martin and me. We were ‘ta paithia’: the children. (I was twenty eight and Martin was a couple of years older.) We had the function of being a sort of comedy duo: innately hilarious, in the way that foreigners are always funny, but even more so by dint of not being grandfathers. As well, I was a woman: a joke in itself. And Martin was tall and skinny and had long hippy hair and — weirdest of all — he spoke Greek like a Greek. Who’d ever heard of a foreigner who could do that? And — even more impressive— he knew the score of every Olimpiakos victory back to 1925 when the club was founded. And so, in the manner of court jesters or fools, we earned our place at the table of the grandfathers.

We were first invited there by a grandfather named Manolis, who at the age of forty-six was by far the youngest grandfather among the clientele. The oldest was reputedly aged 105. He was still a big man, but his much-wrinkled head had sunken into his neck so that he resembled a Galapagos tortoise. Appropriately, the place itself was also very old, and was in the old Turkish part of town. As if it had been tunnelled rather than constructed, it took the form of a huge dark cavern with a curved ceiling, which sort of echoed the shape of the huge wooden barrel of krasi at the back. Here the tables were small and metal, café-style, and at each there sat one or two grandfathers, of varying ages, but mostly seventy-plus. The proprietor once again was a woman but, unlike the widow at Astros, she did not even go through the motions of providing food. She just served wine, in small metal beakers. Of course, in Greece, it is regarded as barbaric to drink xiro sfyri — literally ‘dry hammer’ (don’t ask! And apologies for my mis-transliteration) and meaning ‘without eating’. But no worries! As the evening wore on, the daughters and granddaughters and great-granddaughters of the grandfathers would arrive with their dinners — little bowls or plates with maybe a few whitebait or sardines, or perhaps a spoonful of stewed chicken, some green beans in tomato sauce, a wedge of soft white mizithra cheese, a bowl of brown fava, some horta, a saucer of home-grown olives, or half a dozen dolmathakia…

As Martin and I sat, always with Manolis, and drank and talked (or Martin talked and I smiled to pretend I was following), the grandfathers would send us tastes of their dinners. One after another. Each one proudly insisting that we try the food that had come from his family. And so we had a nightly banquet of the best of Greek home cooking, served in tiny portions, meze-style.

Kolokithokeftedes… kotopoulo kokkinisto… phylla… revithia me melitzanes… gemista… keftedakia… patates sto fourno… hortopitta… fasolakia… giouvetsi… lachanodolmades… spanakorizo…kounoupidi kapama…

‘Orea!’ We could proclaim as we tested each dish. ‘Para polli orea!’ And it was indeed wonderful — truly wonderful food.

In those days, Greece was still a very poor country, and the food was still the food of the poor: food made with few ingredients, but with a great deal of time and love. Food cooked on a single gas burner, or perhaps in the baker’s oven. Food bought fresh at market each day, then cooked and eaten that same day, because there was no refrigerator to store it in.

That is what Greek food is, to me.

I was recently given a Greek cook book that begins with a section called ‘Breakfast and Brunch’.

Breakfast? If you’re lucky, a Greek breakfast is a rusk with a smear of olive oil.

Brunch? No such word.

And so to Lamb with Nonsense…

In those days, very few Greeks could read or write English, or at least not in the kinds of places that Martin and I frequented, and Greek-English dictionaries were also rare, and basic in the extreme. (No, dear, there was no such thing as Google translate.) So the English translations in menus would often be very idiosyncratic, not to mention mysterious.

My all-time-favourite was a dish called ‘Lamb with Nonsense’. It featured on a menu in the port-town of Volos, in a list with the usual Lamb with Potatoes, Lamb with Beans, Lamb with Eggplant, Lamb with Peppers…

Lamb with Nonsense?

On the Greek side of the menu, it was listed as Arni me Kolokithia, and even I had enough Greek to know that that meant ‘Lamb with Zucchini’ (or pumpkins or squash). But Martin explained that Kolokithia could also be used for something that was, well, ridiculous. And because of the phallic appearance of zucchini, there was a somewhat ribald association with using the word in this way. Thus a Greek might exclaim ‘Kolokithia!’ as an Aussie might say ‘Balls!’

Nonsense, indeed.

Nowadays, I am sad to find this sort of endearing mistake disappearing from menus, as Greek restaurants become ever more geared to tourists. But of course, this is not the only thing to disappear.

While there is nothing wrong with grilled souvlaki, or the perennial moussaka (always pronounced with the accent on the wrong syllable) or the misnamed ‘Greek salad’, a lot of the old labour-intensive, slow-cooked and often meatless dishes are not seen any more. Well, they’re not seen in restaurants.

I am sure, however, that somewhere in Greece, there are still grandfathers, and even grandmothers, feasting on delicious dishes of zucchini fritters, chicken in tomato sauce, macaroni with mince, chickpeas with eggplant, tiny meatballs, wild-green pies, cabbage rolls, spinach rice, potatoes swimming in lemon and oil… And possibly even Lamb with Nonsense.

Nadia

Thank you for the wonderful memories of Greece travel in the 1970s

Wendy and I must have must have crossed paths with you several times

Crete in 1977

Volos in 1971

Peloponnese in 1973

and every year of the 1970s on islands somewhere else

including Kalymnos in 1972

Finally i am reminded of living and working in Soho in the 70s when the best Greek lamb was served in a grimy basement in Frith Street and called "Jimmys"

Now that another story..!

Mike Ranger

After 6 months in France where restaurants seemed to serve steak frites and not much else, we were desperate for pulses, beans, vegetables. On our first night in Rhodes to visit my husband’s sister, we were taken to a taverna where we fell upon wonderful vegetarian food - chickpeas stewed with tomato, stuffed zucchini and peppers, dusky, bitter olives. Just wonderful!