‘I was in the front room upstairs when I heard someone on the balcony say “Here they are!” I looked out the door and saw the street full of police with drawn revolvers firing up into the balcony at us.’

Who is speaking? Where is this? What the hell is happening?

When I’m writing history, I like to work as much as possible from primary documents rather than secondary sources. But, like all historians, I usually begin my search with some references compiled from other historians’ notes or bibliographies.

Despite having this initial shopping list, once I start work in libraries or archives I am always hoping to find a document that no other historian has ever discovered. It’s rare for this to happen, but it is possible.

On one occasion, I hit pay-dirt. I remember it vividly.

It was 1972. Yes, the famous Whitlam year, but this was in the early months so it wasn’t Time yet: Australians were still living under the government that had come to power in the year of my birth. Then aged twenty-three, I was in the second year of researching my Masters thesis on the radical organisations and protests of unemployed workers in New South Wales in the Great Depression. Secondary sources were very limited: at that time, only three books dealing with the Great Depression in Australia had been published . My main resources were newspapers —the capitalist press (Sydney Morning Herald, Smith’s Weekly, Sun, Truth) and the leftist press (Labor Daily, Workers’ Weekly) — and the odd socialist or Communist pamphlet or publication. All, of course, were only available in what we now call ‘hard copy’ (a term that did not yet exist).

Not only were there no digital sources of information (whether Wikipedia or Trove) but library catalogues took the form of index cards. You could search by broad subjects (e.g. ‘Great Depression’; ‘Communist Party of Australia’), but you couldn’t look up ‘unemployed workers’ resistance’, for example. Mostly, you searched by names of authors, but most of the publications I needed were by Anon. Through reading the Workers’ Weekly, I knew the names of Communist Party activists from the 1930s, and I used to trawl for their names. Most of these old comrades had died, and occasionally families had donated Dad’s papers to a library.

So on this day in the autumn of 1972 I had gone to Canberra to do some work in the Archives of Business and Labour at the Australian National University. It was a standard boring day of searching blindly through archival darkness, punctuated every so often by a cigarette break but not by a coffee: in 1972, we didn’t have coffee in Australia (or not what we now call coffee).

Fingering through the catalogue cards from A to Z, I had got up to the ‘T’s when I thought I maybe recognised the name of Alan Thorne. Wasn’t he a Party member? I called up the file, on spec. Opened the box of musty and uncatalogued papers. And discovered the typed statements made by eighteen activists who had been arrested on 19 June 1931 while defending a house in the Sydney suburb of Newtown that was under order of eviction. Part of the file of case notes compiled by the men’s defence solicitor, Christian Jollie Smith, these statements were voices speaking directly from the past. One of the ‘pickets’ (as the occupiers called themselves) in the house at 143 Union Street that day was John Stace:

I was in the front room upstairs when I heard someone on the balcony say “Here they are!” I looked out the door and saw the street full of police with drawn revolvers firing up into the balcony at us. We started throwing bricks in defence of ourselves. I was standing behind and a bit to the right of Gabbit when he grabbed his left arm saying, ‘I am hit.’ I then dropped on my hands and knees to avoid the bullets and backed to the door leading to the stairs.

While Stace was making his way down the stairway through another barrage of bullets and into the front room of the house, he heard the police ‘bashing the back door in’.

When the police got into the house they batoned us unmercifully whether we showed fight or not, calling us Communist Bs, and saying, ‘I’ll give you red Russia you bastards.’ I was knocked over in the front room, a policeman put his foot on me and batoned me while I lay on the floor.

As I sat that day in the archive and read the accounts by Stace and his seventeen fellow-pickets, I was astonished that something like this could have happened in Australian history, and only forty years before, and yet I had never heard of it. Although I myself had been bashed by police in anti-Vietnam and anti-Apartheid struggles, and had even been arrested on a few occasions, I had never been shot at by the coppers!

There was too much material for me to record in my handwritten notes so I arranged for photocopies to be made of the documents, and a day or so later returned home. ‘Home’ being at that time the Sydney suburb of Newtown.

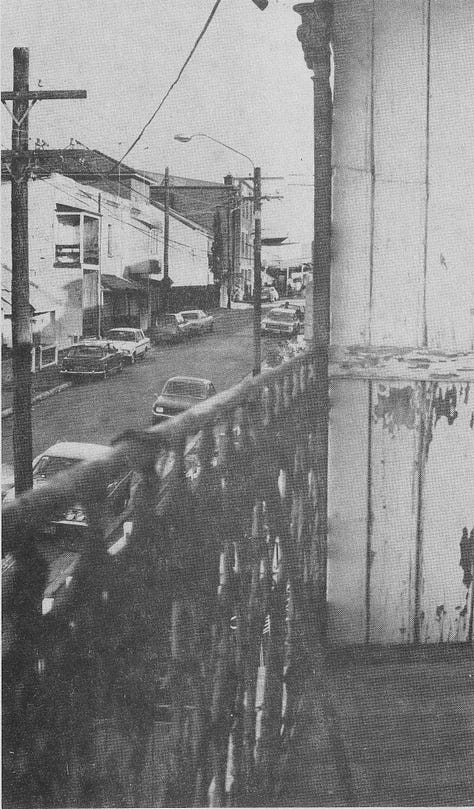

A former history tutor had been fond of saying that a historian’s best tool is a good pair of boots. So I donned my boots and walked the mile or so (we didn’t yet have kilometres in Australia) from my house to 143 Union Street, which I discovered to be one of two adjoining two-storey terrace houses. In 1972 the gentrification and greening of Sydney’s inner-west had not begun, so the streetscape was essentially as it would have been in 1931. Through the power of association I had imagined that the street’s name was connected with industrial unionism, but as soon as I got there I realised that this long and narrow roadway, which cuts diagonally between the two major thoroughfares of King Street and Erskineville Road, is the union between the suburbs of Newtown and Erskineville. (OK, from the 1840s there was a nearby pub called ‘The Union’, but this surely got its name because the street is a union.)

The central location of the house which a band of activists of the Unemployed Workers’ Movement chose to defend gave this anti-eviction campaign a particularly large base of community support on which to draw. It is an archetypical example of how geography can shape history.

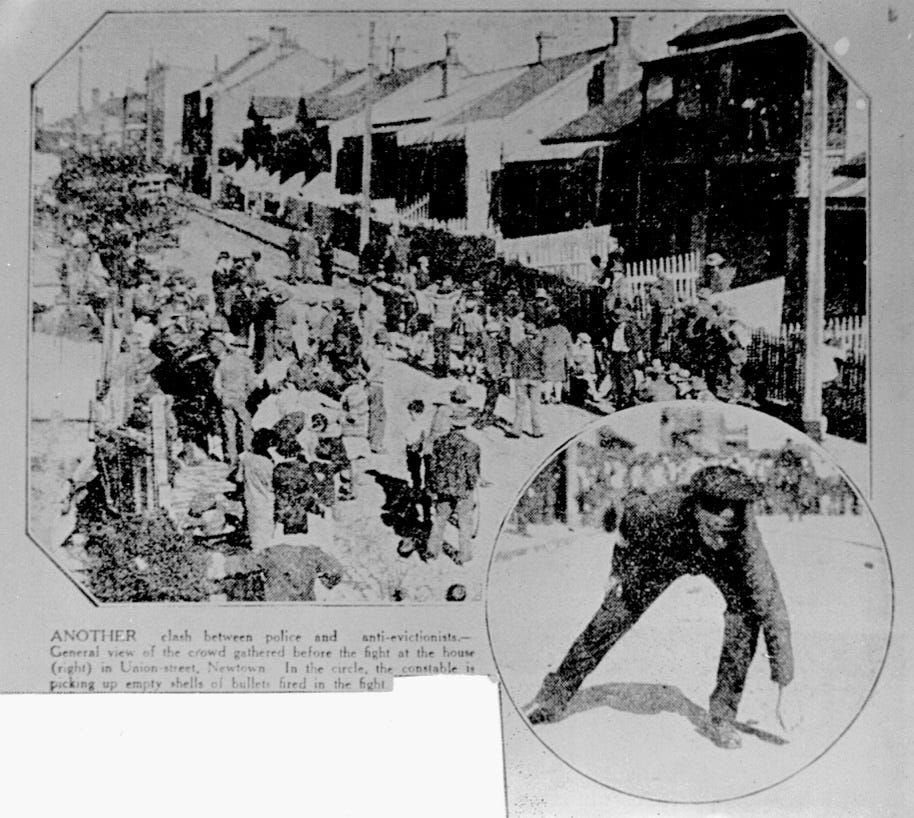

Researching newspaper accounts of this event, I discovered that the Union Street battle was the last of four militant anti-eviction campaigns staged by the UWM in Sydney in the winter of 1931: first at Redfern (30 May), next at Leichhardt (5 June), then at Bankstown (17 June) and, two days later, at Newtown.

At Redfern, the police had threatened the tenant’s wife with their revolvers, but at Bankstown the police had fired their guns, wounding two pickets (one an Aboriginal man, Richard Eatock). After the first two shows of resistance, the Sun newspaper had mounted a Red Scare campaign, claiming that Communists, ‘under orders from Moscow’, were ‘working the [unemployed] into a state of ferment’ and instructing them in ‘offensive measures against the police’, with the result that ‘a very large measure of civil commotion, if not violent rioting’ was imminent.

As things turned out, the Revolution did not happen in Australia (yet again) and the anti-eviction campaign fizzled out soon after the Newtown incident, when Labor premier Jack Lang made a few token changes to the rental laws and it took people a while to realise that nothing had changed (yet again). However, in terms of conflict between the State and non-Indigenous Australians, the battles that took place in the suburbs of Newtown and Bankstown in June 1931 were second only to what had happened in the armed struggle of the Eureka Stockade of 1854. This historical connection had been understood by the unemployed combatants themselves: the fibro cottage at the centre of the struggle at Bankstown was turned into a fortress with sandbags and barbed wire, and it bore a sign renaming it ‘The Eureka Stockade’. The house at 143 Union Street Newtown was similarly fortified, and over the weeks of the campaign it became a de facto community centre, with regular street meetings and gatherings at which there were singsongs as well as political speeches, and bowls of soup were dished up by the stalwart women of the Workers’ International Relief. Although the Unemployed Workers Movement, which was mounting the anti-eviction campaign, was a Communist Party ‘fraternal’, the Union Street pickets had broad neighbourhood support.

By Friday 19 June 1931, the house had been occupied for a few weeks. It was not known exactly when the warrant for eviction would be executed but a small street meeting was in progress when the busload of eighty police arrived around noon and started firing off their guns at the house. The noise of bullets immediately brought people rushing to the scene from across the neighbourhood. Within a short time, according to the Sydney Morning Herald, ‘a crowd hostile to police… filled the street for a quarter of a mile on each side of the building until squads of police drove them back about 200 yards’. So tightly packed were these supporters that a 43-year-old man described as ‘a manufacturer’ had a heart attack and died in the crush. Meanwhile, inside the house the battle described by John Stace and his comrades was in full swing.

For me, these activists were like the long-forgotten ‘casualties of history’ that E.P. Thompson had written about in The Making of the English Working Class (my personal Bible, as far as historiography is concerned). Yet while I was proud to have uncovered and documented their struggle, I had at that time no intention of taking their story any further. When I finished my thesis, I left it on the floor of my supervisor’s office. I was off to Greece, to write fiction!

***

Fast forward to early 1979. I had not long been back in the country when Jill Roe, then President of the Sydney History Group, asked me to write a chapter for a book she was editing. I had an open brief in regard to subject matter but it was a no-brainer to return to the anti-eviction battles. At that time, I was myself on the dole and I was an activist in a tiny left-wing-fringe organisation called the Unemployed People’s Union. UPU, or ‘Up You!’ as we thought of it, was devoted to making life a misery for Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, the snooty squatter from Victoria’s Western District who, in his Alfred Deakin Lecture of July 1971, had said that ‘Life was not meant to be easy’ for the unemployed — as meanwhile his government reduced the value of the dole and introduced a discriminatory ‘Work Test’ aimed at forcing people off benefit. So, what with living in Newtown and being a radical ratbag, I felt a certain personal connection with the Newtown anti-evictionists.

I barely had time to sort my research notes for Jill Roe’s article when again I struck gold. By an extraordinary coincidence, the poet John Forbes happened to rent the house at 143 Union Street Newtown!

As soon as I heard where John and some mates had moved, I raced to the scene of the crime and searched for evidence. There were no bullet holes in the plaster, let alone imprints of blood-stained hands crawling up the walls, but the unrenovated terrace was structurally identical to how it had been in 1931.

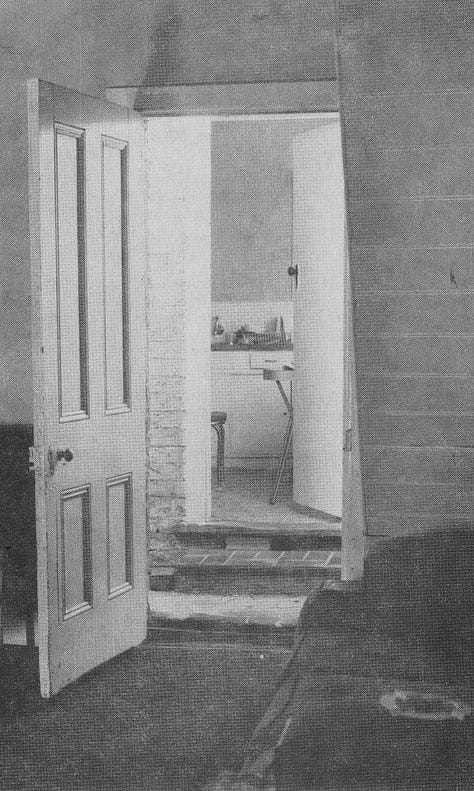

From its narrow facade, the door opened straight into the front room, and onto a boxy staircase. A second small downstairs room opened onto a covered breezeway; beyond this was a scullery.

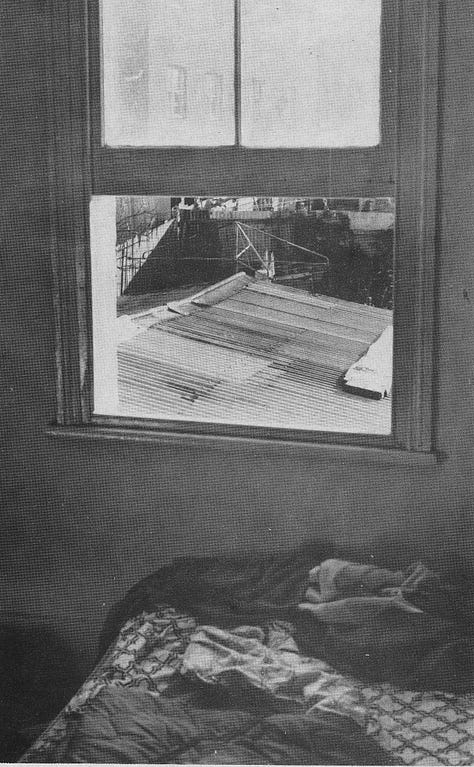

Upstairs, the front room had a single door opening to a narrow balcony; the partition between this balcony and the balcony of the adjoining terrace was made of wood. (Subsequently outlawed by fire regulations.) The back room had a window opening onto the roof of the scullery and breezeway.

By being in the place where the battle had happened, I could understand the pickets’ accounts far better that I had just by reading them. In particular, I was instantly able to see how the police had simultaneously forced their way through the barricades at four entry points: the front door, the back door, across the scullery roof to the upstairs back bedroom, and through the wooden partition that divided the balcony of 143 from the adjoining terrace house, where — significantly — the landlady lived.

‘Why don’t you get Mark Ray to take some photos to illustrate your article?’ Forbes suggested.

Within a few years, Mark Ray would become a professional journalist and photographer, and he is now the author of a number of fantastic photographic cricket books (he also played cricket at state-level), but at that time the notable thing about Mark Ray was that he had a camera! It was an unusual possession, in those olden days. So Mark kindly met me at 143 Union Street and took high quality black and white interior photographs to illustrate key sites mentioned in the pickets’ accounts.

When Mark complained about how difficult it was to get far enough back in the rooms to take a good photo, this further brought home to me how cramped the house was, and how crowded it must have been with eighteen pickets and perhaps as many as forty police locked in what the Sydney Morning Herald called ‘terrible hand-to-hand combat’:

Wielding bludgeons improvised from iron bars, lead piping, palings, chairs and wooden batons … the Communists made frantic efforts to repel the invading police… The room was absolutely bathed in blood. Insensible men lay on the floor while comrades and foes alike trampled on them. The walls were spattered and daubed with bloodstained hands.

As I was writing my article, a neighbour who was an out-of-work architect also came to 143 Union Street with me and drew up a house plan, into which I was able to correlate the statements of the pickets.

Through this time of historical enquiry, I was also engaged in political praxis. Thus my calendar for Monday 6 August 1979 reminds me to ‘Measure John’s house’ as well as to pay a visit to the dole office to lodge my fortnightly Work Test form and to go to ‘UPU Meeting 7 pm’. The next Monday evening, the Unemployed People’s Union staged a demo against Malcolm Fraser, who was attending a gala dinner at the Wentworth Hotel. Our protest, held on the street outside the venue, took the form of a 1930s soup kitchen at which we sang Depression-era songs and gave out paper cups of soup to hungry dole bludgers; it was hardly our fault if some of Malcolm’s fellow-guests ended up with hot pea potage down their dinner jackets. The next day, 14 August, my calendar records ‘Ring Issy Wyner’ (he had been an unemployed activist in the 1930s and was now my mentor) and also ‘Footnotes & Conclusion’. Obviously, I had nearly finished my article. The next year, my piece would appear in Twentieth Century Sydney — Studies in Urban & Social History (published by Hale & Iremonger).

A few years later, still on the dole, the story of the Newtown battle inspired my novel, The House that was Eureka (published by Penguin in 1985; re-published as a Text Classic in 2013). In 2001 I collaborated with colleague Drew Cottle to produce a chapter about Sydney’s Anti-Eviction Movement in Labour & Community (University of Wollongong Press). A few years ago I talked about the Union Street campaign as part of a feature on the Unemployed Workers’ Movement for the People’s History podcast. And in March this year, I gave a paper about the Newtown siege at the Radical Sydney conference.

Over the years, I have sometimes seen other people’s articles about the Union Street battle, sometimes acknowledging my research, usually not — but never mind. At least the story is being told, I tell myself.

But to what purpose, I sometimes wonder…

***

In 2010, when 143 Union Street was up for sale, the real estate agency website invited buyers to ‘OWN YOUR OWN PART OF HISTORY’ and went on to state that the house was the site of ‘the most sensational eviction battle Sydney has ever known’. (A phrase from my Twentieth Century Sydney article, but never mind.)

Among the house’s selling features (according to a puff piece in the Daily Telegraph) were ‘bullet holes in the upstairs bedroom’. (Not when I last looked, but never mind.)

‘Simply move in to enjoy the magical lifestyle with so much of Newtown's history’, the real estate advertisement concluded.

More recently (November 2024), an estate agent’s online piece promoting the area extolled ‘the Siege of Union Street’ in which ‘Members of an unemployed union barricaded themselves into the house, fighting with police for several days’. (Several days? Never mind.) ‘Shots were fired, eight police needed ambulance treatment and 18 arrests were made.’ (Here only the wallopers are injured. Never mind.) Quoting ‘an academic paper’, he described what had happened in Union Street on 19 June 1931 as ‘the biggest spontaneous demonstration of the 1930s’. (I’d said ‘in Sydney’, but never mind). He added that ‘the premier then introduced legislation to prevent people being thrown out of their homes’. I didn’t say that.

Sold in 2010 for $875,000, Number 143 is now valued by Property-dot-com at $1,869,000. Expected weekly rental income is $1050.

No way could someone like John Forbes afford to live here now, let alone John Stace.

***

After the battle, the Sydney Morning Herald published a list of injuries suffered by the pickets:

Joe Gabriel (Garbutt), 36, of May Street Newtown, gunshot wound in the left arm; Bruno Ubranski, 50, of Bourke Street Surry Hills, head injuries; Patrick Storen, 26, of Fitzroy Street Surry hills, fractured left hand; John Murphy, 39, of Phillip Street Enmore, head injuries; Robert Clarke, 27 of Hynes Street Darlington, head injuries; Percy Riley 33 of Victoria Street Lewisham, concussion and lacerations to the head; Raymond Dare, 26 of Alice Street Newtown, head injuries; Len Emmerton, 39 of Regent Street Newtown, head injuries; Reg Hawkins, 33, of Rochford Street Erskineville, head injuries; Henry Hayley, 20, of Adelaide Street Surry Hills, head injuries; Percy Joshua, 29, of Great Buckingham Street Redfern, head injuries; Leslie Goldberg, 31, fractured skull.

Percy Riley, who suffered concussion and lacerations to the head, stated:

After a while I was handcuffed, both hands behind the back. While being taken out to the back I was made a target of by the police. I was punched all over the face. One blow dropped me to my knees. I was jerked to my feet and taken out to the yard. After a while we were taken and put in the patrol van and taken to the station. While in the charge room I received another blow on the jaw and was knocked down. I lay there until the ambulance came and we were taken to hospital and put to bed.

As I consider how this campaign for tenants’ rights has been rewritten as capitalist advertising copy, I ponder the market value of the pickets’ injuries.

For a little under two million dollars, you too could ‘OWN YOUR OWN PART OF HISTORY’.

What a riveting read, Nadia. A marvellously detailed archival find, giving direct voice to the experience: ‘wallopers’ being the most accurate description. I love that you went out walking to find the house and get the geography for your history; and that you got access to the interior when John Forbes lived there. The tales that houses tell … and are told about them by writers, and real estate agencies.

Nadia

Thank you for telling this good story

It needs to be told and remembered

This story ,of course , has many similarities today unfortunately....but never mind..!

Mike